What Was the Last Effort to Prevent the South From Seceding?

Facts, data and articles about Secession, i of the causes of the ceremonious war

Secession summary: the secession of Southern States led to the establishment of the Confederacy and ultimately the Ceremonious War. Information technology was the most serious secession movement in the United states of america and was defeated when the Union armies defeated the Confederate armies in the Ceremonious War, 1861-65.

Secession summary: the secession of Southern States led to the establishment of the Confederacy and ultimately the Ceremonious War. Information technology was the most serious secession movement in the United states of america and was defeated when the Union armies defeated the Confederate armies in the Ceremonious War, 1861-65.

Causes Of Secession

Before the Civil War, the country was dividing between North and South. Issues included States Rights and disagreements over tariffs only the greatest split up was on the outcome of slavery, which was legal in the South but had gradually been banned by states north of the Mason-Dixon line. As the Usa acquired new territories in the westward, bitter debates erupted over whether or not slavery would be permitted in those territories. Southerners feared it was only a matter of time before the addition of new non-slaveholding states but no new slaveholding states would give control of the regime to abolitionists, and the establishment of slavery would be outlawed completely. They also resented the notion that a northern industrialist could establish factories, or whatsoever other business organization, in the new territories but agrarian Southern slaveowners could non move into territories where slavery was prohibited because their slaves would then be free .

With the ballot in 1860 of Abraham Lincoln, who ran on a message of containing slavery to where it currently existed, and the success of the Republican Party to which he belonged – the first entirely regional political party in US history – in that ballot, S Carolina seceded on December 20, 1860, the first state to ever officially secede from the United States. Four months afterwards, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Texas and Louisiana seceded as well. Afterwards Virginia (except for its northwestern counties, which broke away and formed the Marriage-loyal land of Westward Virginia), Arkansas, Due north Carolina, and Tennessee joined them. The people of the seceded states elected Jefferson Davis every bit president of the newly formed Southern Confederacy.

Secession Leads To War

The Civil State of war officially began with the Boxing of Fort Sumter. Fort Sumter was a Union fort in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. Later on the U.Due south. Army troops inside the fort refused to vacate it, Confederate forces opened fire on the fort with cannons. It was surrendered without prey (except for two US soldiers killed when their cannon exploded while firing a terminal salute to the flag) but led to the bloodiest war in the nation's history.

A Short History of Secession

From Articles of Confederation to "A More Perfect Spousal relationship." Many people, specially those wishing to support the South's right to secede in 1860–61, have said that when 13 American colonies rebelled against Great Britain in 1776, information technology was an act of secession. Others say the 2 situations were dissimilar and the colonies' revolt was a revolution. The war resulting from that colonial revolt is known every bit the American Revolution or the American State of war for Independence.

During that war, each of the rebelling colonies regarded itself every bit a sovereign nation that was cooperating with a dozen other sovereigns in a relationship of convenience to attain shared goals, the virtually firsthand being independence from Britain. On Nov. 15, 1777, the Continental Congress passed the Manufactures of Confederation—"Sure Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union"—to create "The United states of america of America." That document asserted that "Each State retains is sovereignty, freedom and independence" while entering into "a house league of friendship with each other" for their common defence and to secure their liberties, as well as to provide for "their common and general welfare."

Under the Articles of Confederation, the central regime was weak, without even an executive to pb information technology. Its only political body was the Congress, which could non collect taxes or tariffs (it could ask states for "donations" for the mutual good). It did have the power to oversee foreign relations but could non create an regular army or navy to enforce foreign treaties. Even this relatively weak governing document was not ratified by all the states until 1781. It is an old truism that "All politics are local," and never was that more true than during the early days of the United States. Having just seceded from what they saw equally a despotic, powerful central authorities that was likewise distant from its citizens, Americans were skeptical about giving much power to whatsoever government other than that of their own states, where they could exercise more than direct control. Nevertheless, seeds of nationalism were as well sown in the war: the war required a united effort, and many men who likely would accept lived out their lives without venturing from their own land traveled to other states as part of the Continental Army.

The weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation were obvious almost from the beginning. Strange nations, ruled to varying degrees by monarchies, were inherently contemptuous of the American experiment of entrusting rule to the ordinary people. A government without an army or navy and lilliputian real power was, to them, only a laughing stock and a plum ripe for picking whenever the opportunity arose.

Domestically, the lack of any uniform codes meant each state established its own class of authorities, a chaotic arrangement marked at times past mob rule that burned courthouses and terrorized land and local officials. State laws were passed and almost immediately repealed; sometimes ex mail service facto laws fabricated new codes retroactive. Collecting debts could exist virtually incommunicable.

George Washington, writing to John Jay in 1786, said, "We have, probably, had too adept an opinion of human nature in forming our confederation." He underlined his words for emphasis. Jay himself felt the country had to get "one nation in every respect." Alexander Hamilton felt "the prospect of a number of niggling states, with appearance merely of union," was something "atomic and contemptible."

In May 1787, a Ramble Convention met in Philadelphia to address the shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation. Some Americans felt information technology was an aristocratic plot, simply every state felt a need to do something to improve the situation, and smaller states felt a stronger fundamental regime could protect them against domination by the larger states. What emerged was a new constitution "in order to provide a more perfect union." It established the three branches of the federal government—executive, legislative, and judicial—and provided for two houses within the legislature. That Constitution, though amended 27 times, has governed the United states of america always since. It failed to clearly accost 2 critical issues, however.

It fabricated no mention of the future of slavery. (The Northwest Ordinance, not the Constitution, prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territories, that expanse n of the Ohio River and along the upper Mississippi River.) Information technology also did not include any provision for a procedure by which a state could withdraw from the Union, or by which the Union could be wholly dissolved. To have included such provisions would take been, as some have pointed out, to have written a suicide clause into the Constitution. But the issues of slavery and secession would take on towering importance in the decades to come, with no clear-cut guidance from the Founding Fathers for resolving them.

First Calls for Secession

Post-obit ratification past 11 of the 13 states, the government began operation under the new U.S. Constitution in March 1789. In less than 15 years, states of New England had already threatened to secede from the Union. The first time was a threat to leave if the Assumption Beak, which provided for the federal government to assume the debts of the various states, were not passed. The adjacent threat was over the expense of the Louisiana Purchase. Then, in 1812, President James Madison, the man who had done more any other individual to shape the Constitution, led the United States into a new war with Britain. The New England states objected, for war would cut into their merchandise with United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and Europe. Resentment grew and so strong that a convention was called at Hartford, Connecticut, in 1814, to talk over secession for the New England states. The Hartford Convention was the most serious secession threat up to that fourth dimension, simply its delegates took no activity.

Southerners had also discussed secession in the nation's early years, concerned over talk of abolishing slavery. But when push came to shove in 1832, it was not over slavery merely tariffs. National tariffs were passed that protected Northern manufacturers but increased prices for manufactured appurtenances purchased in the predominantly agricultural S, where the Tariff of 1828 was dubbed the "Tariff of Abominations." The legislature of S Carolina declared the tariff acts of 1828 and 1832 were "unauthorized by the constitution of the U.s.a." and voted them nothing, void and non-bounden on the land.

President Andrew Jackson responded with a Proclamation of Force, declaring, "I consider, then, the ability to annul a constabulary of the United states, assumed by one country, incompatible with the beingness of the Matrimony, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, inconsistent with every principle on which information technology was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed." (Emphasis is Jackson'south). Congress authorized Jackson to apply military force if necessary to enforce the law (every Southern senator walked out in protest before the vote was taken). That proved unnecessary, as a compromise tariff was approved, and South Carolina rescinded its Nullification Ordinance.

The Nullification Crisis, every bit the episode is known, was the most serious threat of disunion the young country had yet confronted. It demonstrated both standing beliefs in the primacy of states rights over those of the federal government (on the part of South Carolina and other Southern states) and a belief that the principal executive had a correct and responsibility to suppress any attempts to give private states the right to override federal law.

The Abolition Movement, and Southern Secession

Betwixt the 1830s and 1860, a widening chasm adult between N and South over the issue of slavery, which had been abolished in all states north of the Mason-Dixon line. The Abolition Movement grew in power and prominence. The slave holding South increasingly felt its interests were threatened, peculiarly since slavery had been prohibited in much of the new territory that had been added west of the Mississippi River. The Missouri Compromise, the Dred Scott Decision case, the issue of Popular Sovereignty (allowing residents of a territory to vote on whether information technology would be slave or free), and John Chocolate-brown's Raid On Harpers Ferry all played a role in the intensifying argue. Whereas once Southerners had talked of an emancipation process that would gradually end slavery, they increasingly took a hard line in favor of perpetuating it forever.

In 1850, the Nashville Convention met from June 3 to June 12 "to devise and prefer some mode of resistance to northern aggression." While the delegates approved 28 resolutions affirming the South's constitutional rights inside the new western territories and similar bug, they essentially adopted a wait-and-see mental attitude before taking whatever desperate activity. Compromise measures at the federal level diminished interest in a second Nashville Convention, simply a much smaller one was held in Nov. It approved measures that affirmed the right of secession but rejected whatsoever unified secession among Southern states. During the brief presidency of Zachary Taylor, 1849-l, he was approached by pro-secession ambassadors. Taylor flew into a rage and alleged he would raise an ground forces, put himself at its head and force any state that attempted secession back into the Union.

The spud famine that struck Ireland and Germany in the 1840s–1850s sent waves of hungry immigrants to America's shores. More of them settled in the North than in the South, where the existence of slavery depressed wages. These newcomers had sought refuge in the United States, not in New York or Virginia or Louisiana. To almost of them, the U.S. was a unmarried entity, not a collection of sovereign nations, and arguments in favor of secession failed to move them, for the about function.

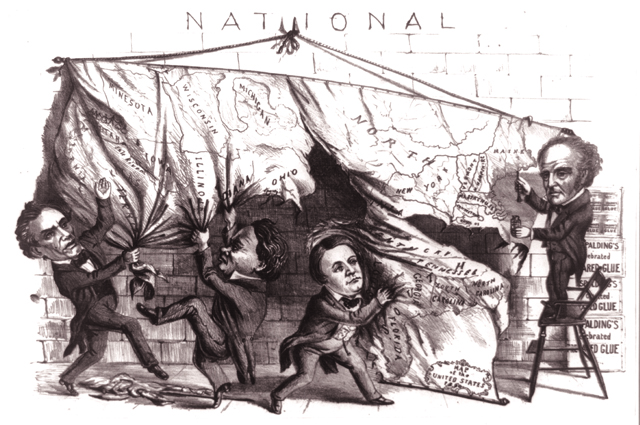

The Ballot Of Abraham Lincoln And Nullification

The U.Due south. elections of 1860 saw the new Republican Political party, a exclusive party with very little support in the Southward, win many seats in Congress. Its candidate, Abraham Lincoln, won the presidency. Republicans opposed the expansion of slavery into the territories, and many party members were abolitionists who wanted to come across the "peculiar establishment" ended everywhere in the United States. S Carolina again decided information technology was time to nullify its agreement with the other states. On December. twenty, 1860, the Palmetto State approved an Ordinance of Secession, followed by a declaration of the causes leading to its decision and some other certificate that concluded with an invitation to form "a Confederacy of Slaveholding States."

The South Begins To Secede

South Carolina didn't intend to get it alone, as it had in the Nullification Crunch. Information technology sent ambassadors to other Southern states. Shortly, six more states of the Deep South—Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Texas and Louisiana—renounced their compact with the Us. After Amalgamated arms fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion. This led four more states— Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee—to secede; they refused to accept up arms against their Southern brothers and maintained Lincoln had exceeded his constitutional powers past not waiting for approval of Congress (as Jackson had done in the Nullification Crisis) before declaring war on the Due south. The legislature of Tennessee, the last state to go out the Union, waived whatever opinion as to "the abstract doctrine of secession," but asserted "the right, as a free and independent people, to modify, reform or abolish our form of government, in such manner equally we think proper."

In addition to those states that seceded, other areas of the country threatened to. The southern portions of Northern states adjoining the Ohio River held pro-Southern, pro-slavery sentiments, and there was talk within those regions of seceding and casting their lot with the Southward.

A portion of Virginia did secede from the Old Dominion and formed the Matrimony-loyal state of Westward Virginia. Its creation and admittance to the Union raised many constitutional questions—Lincoln's cabinet split 50–50 on the legality and expediency of admitting the new state. Merely Lincoln wrote, "It is said that the admission of West-Virginia is secession, and tolerated simply because information technology is our secession. Well, if we call it by that name, there is still difference plenty between secession confronting the constitution, and secession in favor of the constitution."

The Ceremonious War: The End Of The Secession Movement

Four bloody years of state of war ended what has been the nigh significant attempt by states to secede from the Union. While the Due south was forced to abandon its dreams of a new Southern Confederacy, many of its people accept never accepted the idea that secession was a violation of the U.South. Constitution, basing their arguments primarily on Article 10 of that constitution: "The powers not delegated to the United States past the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people."

Ongoing Calls For Secession & The Eternal Question: "Tin A State Legally Secede?"

The ongoing debate continues over the question that has been asked since the forming of the United States itself: "Can a state secede from the Union of the United states?" Whether information technology is legal for a land to secede from the United States is a question that was fiercely debated earlier the Civil State of war (see the article below), and even now, that fence continues. From time to time, new calls have arisen for one country or another to secede, in reaction to political and/or social changes, and organizations such as the League of the South openly support secession and the germination of a new Southern republic.

Articles Featuring Secession From History Net Magazines

Featured Commodity

Was Secession Legal

Southerners insisted they could legally bolt from the Wedlock.

Northerners swore they could not.

War would settle the thing for good.

Over the centuries, various excuses have been employed for starting wars. Wars have been fought over country or honor. Wars have been fought over soccer (in the case of the conflict between Honduras and El salvador in 1969) or even the shooting of a pig (in the case of the fighting between the U.s. and Great britain in the San Juan Islands in 1859).

But the Civil War was largely fought over equally compelling interpretations of the U.S. Constitution. Which side was the Constitution on? That'due south hard to say.

The interpretative argue—and ultimately the state of war—turned on the intent of the framers of the Constitution and the meaning of a single word: sovereignty—which does not actually appear anywhere in the text of the Constitution.

Southern leaders like John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis argued that the Constitution was substantially a contract betwixt sovereign states—with the contracting parties retaining the inherent authority to withdraw from the agreement. Northern leaders similar Abraham Lincoln insisted the Constitution was neither a contract nor an agreement between sovereign states. It was an agreement with the people, and once a state enters the Spousal relationship, it cannot go out the Union.

Information technology is a touchstone of American ramble constabulary that this is a nation based on federalism—the matrimony of states, which retain all rights non expressly given to the federal regime. After the Declaration of Independence, when most people still identified themselves not equally Americans only as Virginians, New Yorkers or Rhode Islanders, this union of "Free and Independent States" was divers as a "confederation." Some framers of the Constitution, like Maryland's Luther Martin, argued the new states were "separate sovereignties." Others, similar Pennsylvania's James Wilson, took the contrary view that united states "were contained, not Individually just Unitedly."

Supporting the individual sovereignty claims is the vehement independence that was asserted by states under the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, which actually established the name "The U.s.." The lease, however, was careful to maintain the inherent sovereignty of its blended country elements, mandating that "each state retains its sovereignty, liberty, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and correct, which is not past this Confederation expressly delegated." It affirmed the sovereignty of the corresponding states by declaring, "The said states hereby severally enter into a house league of friendship with each other for their common defence [sic]." There would seem piffling question that the states agreed to the Confederation on the express recognition of their sovereignty and relative independence.

Supporting the later view of Lincoln, the perpetuality of the Wedlock was referenced during the Confederation menstruation. For example, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 stated that "the said territory, and u.s.a. which may exist formed therein, shall forever remain a part of this confederacy of the United States of America."

The Confederation produced endless conflicts equally various states issued their own coin, resisted national obligations and favored their own citizens in disputes. James Madison criticized the Articles of Confederation as reinforcing the view of the Union as "a league of sovereign powers, non as a political Constitution by virtue of which they are become i sovereign ability." Madison warned that such a view could lead to the "dissolving of the U.s. altogether." If the affair had concluded there with the Manufactures of Confederation, Lincoln would have had a much weaker case for the court of constabulary in taking up arms to preserve the Union. His legal instance was saved by an 18th-century bait-and-switch.

A convention was called in 1787 to amend the Articles of Confederation, but several delegates somewhen concluded that a new political structure—a federation—was needed. As they debated what would become the Constitution, the status of the states was a primary concern. George Washington, who presided over the convention, noted, "It is apparently impracticable in the federal regime of these states, to secure all rights of independent sovereignty to each, and yet provide for the interest and condom of all." Of form, Washington was more concerned with a working federal government—and national army—than resolving the question of a state'due south inherent right to withdraw from such a union. The new regime forged in Philadelphia would have clear lines of dominance for the federal organisation. The premise of the Constitution, however, was that states would however agree all rights not expressly given to the federal government.

The final version of the Constitution never really refers to the states as "sovereign," which for many at the time was the ultimate legal game-changer. In the U.S. Supreme Courtroom'southward landmark 1819 decision in McCulloch v. Maryland, Chief Justice John Marshall espoused the view later on embraced past Lincoln: "The government of the Union…is emphatically and truly, a regime of the people." Those with differing views resolved to exit the matter unresolved—and thereby planted the seed that would grow into a full civil war. But did Lincoln win by force of arms or force of argument?

On January 21, 1861, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi went to the well of the U.S. Senate one last time to announce that he had "satisfactory evidence that the State of Mississippi, by a solemn ordinance of her people in convention assembled, has declared her separation from the United States." Before resigning his Senate seat, Davis laid out the basis for Mississippi's legal merits, coming down squarely on the fact that in the Declaration of Independence "the communities were declaring their independence"—not "the people." He added, "I take for many years advocated, every bit an essential attribute of state sovereignty, the right of a state to secede from the Matrimony."

Davis' position reaffirmed that of John C. Calhoun, the powerful South Carolina senator who had long viewed the states as independent sovereign entities. In an 1833 speech upholding the right of his dwelling house state to nullify federal tariffs it believed were unfair, Calhoun insisted, "I proceed the basis that [the] constitution was fabricated by us; that information technology is a federal matrimony of the States, in which the several States still retain their sovereignty." Calhoun allowed that a state could be barred from secession by a vote of 2-thirds of the states nether Commodity V, which lays out the procedure for amending the Constitution.

Davis' position reaffirmed that of John C. Calhoun, the powerful South Carolina senator who had long viewed the states as independent sovereign entities. In an 1833 speech upholding the right of his dwelling house state to nullify federal tariffs it believed were unfair, Calhoun insisted, "I proceed the basis that [the] constitution was fabricated by us; that information technology is a federal matrimony of the States, in which the several States still retain their sovereignty." Calhoun allowed that a state could be barred from secession by a vote of 2-thirds of the states nether Commodity V, which lays out the procedure for amending the Constitution.

Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, 1861, was ane of the least auspicious beginnings for any president in history. His election was used as a rallying cry for secession, and he became the head of a state that was falling apart even equally he raised his manus to take the oath of function. His first inaugural accost left no doubt about his legal position: "No State, upon its own mere motility, tin can lawfully exit of the Union, that resolves and ordinances to that effect are legally void, and that acts of violence, inside any State or States, against the authority of the Usa, are insurrectionary or revolutionary, according to circumstances."

While Lincoln expressly called for a peaceful resolution, this was the final straw for many in the South who saw the speech every bit a veiled threat. Clearly when Lincoln took the adjuration to "preserve, protect, and defend" the Constitution, he considered himself spring to preserve the Union as the physical cosmos of the Declaration of Independence and a central subject of the Constitution. This was made evidently in his next major legal argument—an accost where Lincoln rejected the notion of sovereignty for states equally an "ingenious sophism" that would lead "to the complete destruction of the Union." In a Quaternary of July message to a special session of Congress in 1861, Lincoln declared, "Our States have neither more than, nor less power, than that reserved to them, in the Union, by the Constitution—no one of them ever having been a State out of the Union. The original ones passed into the Union fifty-fifty before they cast off their British colonial dependence; and the new ones each came into the Union directly from a condition of dependence, excepting Texas. And even Texas, in its temporary independence, was never designated a State."

It is a vivid framing of the effect, which Lincoln proceeds to narrate as nothing less than an attack on the very notion of democracy:

Our pop government has ofttimes been called an experiment. Two points in it, our people have already settled—the successful establishing, and the successful administering of it. One notwithstanding remains—its successful maintenance against a formidable [internal] endeavour to overthrow it. It is at present for them to demonstrate to the globe, that those who can fairly carry an election, tin also suppress a rebellion—that ballots are the rightful, and peaceful, successors of bullets; and that when ballots have fairly, and constitutionally, decided, there tin can be no successful appeal, back to bullets; that at that place can be no successful entreatment, except to ballots themselves, at succeeding elections. Such will be a slap-up lesson of peace; instruction men that what they cannot take past an election, neither tin they take it by a war—instruction all, the folly of being the beginners of a war.

Lincoln implicitly rejected the view of his predecessor, James Buchanan. Buchanan agreed that secession was not allowed under the Constitution, but he besides believed the national government could non use force to go on a state in the Union. Notably, yet, it was Buchanan who sent troops to protect Fort Sumter six days after Southward Carolina seceded. The subsequent seizure of Fort Sumter by rebels would push Lincoln on April 14, 1861, to phone call for 75,000 volunteers to restore the Southern states to the Union—a decisive move to state of war.

Lincoln showed his gift as a litigator in the July 4th address, though it should be noted that his scruples did not stop him from clearly violating the Constitution when he suspended habeas corpus in 1861 and 1862. His argument besides rejects the suggestion of people similar Calhoun that, if states can modify the Constitution under Article Five past autonomous vote, they can agree to a country leaving the Union. Lincoln's view is absolute and treats secession equally nothing more than than rebellion. Ironically, equally Lincoln himself best-selling, that places the states in the same position as the Constitution'due south framers (and presumably himself as King George).

But he did notation one telling departure: "Our adversaries have adopted some Declarations of Independence; in which, different the good onetime 1, penned by Jefferson, they omit the words 'all men are created equal.'"

Lincoln'south statement was more than convincing, but only up to a point. The South did in fact secede because it was unwilling to accept decisions by a majority in Congress. Moreover, the disquisitional passage of the Constitution may be more important than the condition of united states of america when independence was declared. Davis and Calhoun'southward statement was more than compelling under the Articles of Confederation, where there was no express waiver of withdrawal. The reference to the "perpetuity" of the Spousal relationship in the Articles and such documents as the Northwest Ordinance does not necessarily mean each country is bound in perpetuity, just that the nation itself is so created.

Lincoln'south statement was more than convincing, but only up to a point. The South did in fact secede because it was unwilling to accept decisions by a majority in Congress. Moreover, the disquisitional passage of the Constitution may be more important than the condition of united states of america when independence was declared. Davis and Calhoun'southward statement was more than compelling under the Articles of Confederation, where there was no express waiver of withdrawal. The reference to the "perpetuity" of the Spousal relationship in the Articles and such documents as the Northwest Ordinance does not necessarily mean each country is bound in perpetuity, just that the nation itself is so created.

After the Constitution was ratified, a new government was formed by the consent of u.s.a. that conspicuously established a single national government. While, every bit Lincoln noted, u.s. possessed powers non expressly given to the federal authorities, the federal government had sole power over the defence of its territory and maintenance of the Wedlock. Citizens nether the Constitution were guaranteed free travel and interstate commerce. Therefore it is in disharmonize to suggest that citizens could find themselves separated from the country as a whole by a seceding state.

Moreover, while neither the Declaration of Independence nor the Constitution says states can not secede, they also practice non guarantee states such a correct nor refer to the states every bit sovereign entities. While Calhoun'south argument that Commodity Five allows for irresolute the Constitution is attractive on some levels, Article Five is designed to amend the Constitution, not the Union. A clearly ameliorate argument could exist made for a duly enacted amendment to the Constitution that would allow secession. In such a case, Lincoln would conspicuously take been warring against the democratic process he claimed to defend.

Neither side, in my view, had an overwhelming argument. Lincoln's position was the one most probable to be upheld by an objective court of law. Faced with ambiguous founding and constitutional documents, the spirit of the language conspicuously supported the view that the original states formed a marriage and did not retain the sovereign dominance to secede from that union.

Of course, a rebellion is ultimately a competition of arms rather than arguments, and to the victor goes the statement. This legal dispute would be resolved not by lawyers but by more practical men such as William Tecumseh Sherman and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson.

Ultimately, the State of war Between the States resolved the Constitution'southward meaning for any states that entered the Union after 1865, with no delusions about the contractual understanding of the parties. Thus, fifteen states from Alaska to Colorado to Washington entered in the full agreement that this was the view of the Wedlock. Moreover, the enactment of the 14th Subpoena strengthened the view that the Constitution is a meaty between "the people" and the federal government. The amendment affirms the power of the states to brand their own laws, merely those laws cannot "abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States."

Ultimately, the State of war Between the States resolved the Constitution'southward meaning for any states that entered the Union after 1865, with no delusions about the contractual understanding of the parties. Thus, fifteen states from Alaska to Colorado to Washington entered in the full agreement that this was the view of the Wedlock. Moreover, the enactment of the 14th Subpoena strengthened the view that the Constitution is a meaty between "the people" and the federal government. The amendment affirms the power of the states to brand their own laws, merely those laws cannot "abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States."

In that location remains a split guarantee that runs from the federal regime straight to each American citizen. Indeed, information technology was after the Civil War that the notion of being "American" became widely accepted. People at present identified themselves as Americans and Virginians. While the South had a plausible legal claim in the 19th century, in that location is no plausible argument in the 21st century. That argument was answered by Lincoln on July iv, 1861, and more than decisively at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

Jonathan Turley is one of the nation'due south leading constitutional scholars and legal commentators. He teaches at George Washington University.

Article originally published in the November 2010 result of America's Civil War.

Secession: Revisionism Or Reality

Second: Secession – Revisionism or Reality

Secession fever revisited

We can take an honest look at history, or merely revise information technology to brand it more palatable

Try this version of history: 150 years ago this spring, North Carolina and Tennessee became the last two Southern states to secede illegally from the sacred American Union in order to keep 4 million blacks in perpetual bondage. With Jefferson Davis newly ensconced in his Richmond majuscule just a hundred miles south of Abraham Lincoln'south legally elected government in Washington, recruiting volunteers to fight for his "nation," there could be little incertitude that the rebellion would soon turn bloody. The Marriage was understandably prepared to fight for its own beingness.

Or should the scenario read this way? A century and a half ago, North Carolina and Tennessee joined other brave Southern states in asserting their right to govern themselves, limit the evils of unchecked federal power, protect the integrity of the cotton market from burdensome tariffs, and fulfill the promise of liberty that the nation'southward founders had guaranteed in the Declaration of Independence. With Abraham Lincoln's hostile minority regime at present raising militia to invade sovereign states, there could be fiddling doubt that peaceful secession would soon turn into bloody war. The Confederacy was understandably prepared to fight for its own freedom.

Or should the scenario read this way? A century and a half ago, North Carolina and Tennessee joined other brave Southern states in asserting their right to govern themselves, limit the evils of unchecked federal power, protect the integrity of the cotton market from burdensome tariffs, and fulfill the promise of liberty that the nation'southward founders had guaranteed in the Declaration of Independence. With Abraham Lincoln's hostile minority regime at present raising militia to invade sovereign states, there could be fiddling doubt that peaceful secession would soon turn into bloody war. The Confederacy was understandably prepared to fight for its own freedom.

Which version is true? And which is myth? Although the Civil War sesquicentennial is only a few months old, questions like this, which virtually serious readers believed had been asked and answered l—if not 150—years ago, are resurfacing with surprising frequency. And then-called Southern heritage Web sites are afire with culling explanations for secession that make such scant mention of chattel slavery that the modern observer might remember shackled plantation laborers were ante-paying members of the AFL-CIO. Some of the more than egregious comments currently proliferating on the new Civil War blogs of both the New York Times ("Disunion") and Washington Post ("A House Divided") suggest that many contributors go along to believe slavery had little to exercise with secession: Lincoln had no right to serve as president, they fence; his policies threatened land sovereignty; Republicans wanted to impose crippling tariffs that would have destroyed the cotton industry; it was all almost honor. Edward Brawl, writer of Slaves in the Family unit, has dubbed such skewed retentiveness as "the whitewash explanation" for secession. He is correct.

As Ball and scholars like William Freehling, author of Prelude to Ceremonious War and The Road to Disunion, accept pointed out, all today'due south readers need to exercise in club to understand what truly motivated secession is to study the proceedings of the state conventions where separation from the Matrimony was openly discussed and enthusiastically authorized. Many of these dusty records have been digitized and made available online—discrediting this fairy tale once and for all.

Consider these excerpts. Due south Carolina voted for secession starting time in December 1860, bluntly citing the rationale that Northern states had "denounced as sinful the institution of slavery."

Georgia delegates similarly warned against the "progress of anti-slavery." Every bit delegate Thomas R.R. Cobb proudly insisted in an 1860 address to the Legislature, "Our slaves are the near happy and contented of workers."

Mississippians boasted, "Our position is thoroughly identified with the establishment of slavery—the greatest cloth interest of the world…. There is no choice left u.s. but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Wedlock." And an Alabama newspaper opined that Lincoln's election plainly showed the North planned "to free the negroes and strength amalgamation between them and the children of the poor men of the South."

Certainly the endeavor to "whitewash" secession is not new. Jefferson Davis himself was maddeningly vague when he provocatively asked fellow Mississippians, "Will you be slaves or will you be independent?…Volition you consent to be robbed of your property [or] strike bravely for liberty, property, honor and life?" Non-slaveholders—the bulk of Southerners—were bombarded with similarly inflammatory rhetoric designed to paint Northerners as integrationist aggressors scheming to make blacks the equal of whites and impose race-mixing on a helpless population. The whitewash worked in 1861—but does that hateful that it should be taken seriously today?

From 1960-65, the Civil State of war Centennial Commission wrestled with like problems, and ultimately bowed as well deeply to segregationists who worried that an accent on slavery—much less freedom—would embolden the civil rights movement so get-go to gain national traction. Keeping the focus on battlefield re-enactments, regional pride and uncritical celebration took the spotlight off the real cause of the state of war, and its potential inspiration to modern freedom marchers and their sympathizers. Some members of the national centennial commission actually argued against staging a 100th anniversary commemoration of emancipation at the Lincoln Memorial. Doing and then, they contended, would encourage "agitators."

In a way, information technology is more hard to understand why and so much infinite is again being devoted to this argue. Fifty years have passed since the centennial. The nation has been vastly transformed by legislation and mental attitude. Nosotros supposedly live in a "post-racial era." And simply two years ago, Americans (including voters in the former Amalgamated states of Virginia and North Carolina), chose the kickoff African-American president of the United states of america.

Or is this, perhaps, the real underlying problem—the salt that still irritates the scab roofing this state'south unhealed racial carve up?

Just as some Southern conservatives decried a 1961 emphasis on slavery because it might embolden civil rights, 2011 revisionists may have a hidden agenda of their ain: Vanquish back federal authority, reinvigorate the states' rights movement and maybe turn back the re-election of a black president who has been labeled equally everything from a Communist to a foreigner (non unlike the insults hurled at the freedom riders half a century ago).

Fifty years from now, Americans will either gloat the honesty that animated the Ceremonious War sesquicentennial, or field of study it to the aforementioned criticisms that take been leveled confronting the centennial celebrations of the 1960s. The choice is ours. As Lincoln once said, "The struggle of today is not birthday for today—it is for a vast time to come likewise."

Harold Holzer is chairman of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation.

Secession Articles

[cat totalposts='25' offset='0′ category='1194′ extract='truthful' order='desc' orderby='post_date']

Source: https://www.historynet.com/secession/

0 Response to "What Was the Last Effort to Prevent the South From Seceding?"

Post a Comment